|

|

|

dissecting a scarecrow

Sunday, September 6 2009

In the spectrum of literary non-fiction, the Bible, the collected works of Aristotle, and Hammurabi's Code occupy one extreme: the forever unchanging encapsulation of the wisdom of a time. Humanity moved on and learned and discovered more after those works were set in stone (literally, in the case of Hammurabi's Code), but those works will never reflect that new wisdom. The closest they can ever get to change is translation to new languages as the original languages in which they were written (their old lexical homelands) perish and new languages emerge, allowing translators to nudge the old wisdom into slightly more modern directions, a nudge that can be furthered by, for example, interpreting as allegory ancient accounts originally intended as accurate history.

Further towards mutable on the literary mutable-immutable spectrum is a document like the American Constitution, which was written with the awareness that founders can make errors and conditions can change. So it has provisions inside itself providing a procedure by which it can be modified.

Of course, I've never had any patience with Bonze Age religious works claiming scientific infallibility into an endless future. When it comes to an accounting of reality, it's clear that the account requires constant revision. A holy book might have actually provided a useful (if imperfect) template for explaining reality during the relatively-static ten thousand years between the domestication of wheat and the invention of steam power, but these days such texts are as helpful as learning anatomy by dissecting a scarecrow. For this reason, I've become a firm believer in Wikipedia as a source of wisdom. It lies at the opposite extreme of the literary mutable-immutable spectrum from the Bible. I'm not saying that it's always 100% accurate or that the majority of material in there that won't change as more wisdom comes in (that is, after all, the point). There are people who actively deface Wikipedia pages with references to "poopyheads," and others who slip in references to their sweethearts or enemies. Then there are those who manipulate entries for political or ideological purposes. But most of that stuff is caught an reverted before anyone sees it and such noise represents a small fraction of Wikipedia's content, rarely penetrating beyond charismatic entries and those whose subjects are in the news. Furthermore, bad edits inserting anachronistic (or otherwise flawed information) is often of noticeably poorer quality than their context. You can rely on Wikipedia as you would any encyclopedia, only more so. Its power is that it harnesses the same anti-entropic Darwinian forces as the Scientific Method to forge wisdom out of chaos. It's yet more evidence of why Creationism and the stagnant information model it is based on (in two respects!) are failures.

While I miss certain aspects of the early Web: the anti-commercialism, the tight-knit communities channeled through non-proprietary systems, the existence of Wikipedia in today's Web makes up for their loss. The writing is generally good and the interconnected entries make reading it into an infinite non-linear experience. The experience is was what I was going for (in a limited form) with the Big Fun Glossary, but its scope is endless.

Wikipedia has become a great way for me to refresh my knowledge with the latest wisdom about everything. I was a taxonomic junky as a kid, but I remember wondering how "hard" the science of taxonomy was. How can we be so sure, for example, that a loon is one of the most primitive birds? The divisions between taxa seemed arbitrary and provisional. Now, though, we have the objective truth of DNA comparisons, and the taxonomic wisdom coming from those truths can be found in Wikipedia. Like all science, it's provisional, but it's a lot more solid than the taxonomic hand waving I absorbed as a child. (It turns out, according to Wikipedia, that the duck and the chicken belong to a more primitive clade than does the loon.)

Today I was reading the Wikipedia entry about our own star, the Sun, and yet again I was treated to a strange new mindblowing fact. It turns out that the Sun, even the part in the core that actually carries out fusion, produces an astoundingly small amount of energy per cubic meter: only a quarter watt. This leads to an interesting point: duplicating the Sun's particular fusion mechanism on Earth would be entirely impractical because it would require far too much plasma for the amount of energy produced. Practical Earth-based fusion would require much high energy production rates per unit volume, though of course that leads to containment headaches that the Sun doesn't have to worry about. It turns out that an enormous gravity-bound sphere of plasma 93 million miles away producing energy at a lower per-unit rate than the fermentation of beer is the perfect fusion-based renewable energy solution, though perhaps not if there are seven billion of us.

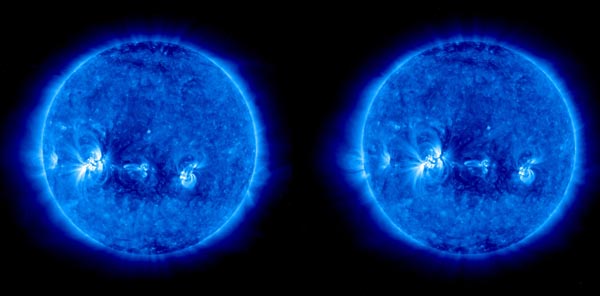

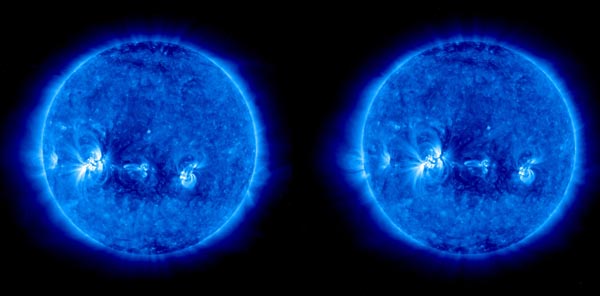

My Wikipedia reading led to an entry about STEREO, a pair of probes sent to provide stereoscopic views of the Sun. This led to NASA's STEREO website, where "cross eyed" stereoscopic photographs were shown, such as this one:

To view it, we are told to cross our eyes until there are three images and then to focus on the virtual image that forms in the middle. I've struggled with stereoscopic images in the past, trying to use viewers and lenses, focusing on a finger held between my eyes and the images, and even placing sheets of paper between my eyes to keep their views entirely separate. But these simple instructions urging me to cross my eyes worked better than anything I'd ever tried before. It was a little tricky to focus on the central image, but once I did it just snapped in place and I could view it at my leisure. The only problem was that I gradually began to develop a headache and my view tended to swim a little whenever I came out of looking at images this way.

Suddenly I was inspired to shoot my own stereoscopic images, so I went around with a camera and snapped some, with varying success. You can look at them here using the method I just described.

|

|

|

This stereoscopic picture of Sylvia on the laboratory deck is the best of the pairs I shot today; the ladder and background behind the rail give it real depth.

|

|

|

|

Eleanor's head pops out towards you in this pair I shot in front of the garage.

|

|

|

|

The tomatoes are sort of a messy screen in this picture, but it's a rewarding pair if you can make the stereoscopic thing happen.

|

|

|

|

Sally. There's not as much angular separation in this pair as I would have preferred. At least she didn't wag her tail between photos.

|

Later I excitedly tried to get Gretchen to look at my stereoscopic pictures, but she said they didn't work for her, that she couldn't cross her eyes. That may be true, but she seemed to give up a bit too easily.

This evening I worked on my database mapping tool, which was a triumph of DHTML development and integration with MySQL back when I created it in late 2007. I'd always been a little unhappy with the algorithm that draws lines between tables in the diagram. I wanted the algorithm to be smarter, to know how to minimize the number of intervening tables it draws across when it draws those lines. So today I dived into the Javascript and figured out how to make it draw to different paths between points on two different tables. The paths are still essentially Cartesian, in that they go over some amount and then up. But now I have it so the lines can be drawn two different ways, either over and up or up and over (or, if the relation goes a different way, over and down or down and over). Now all that was left was writing the routine to figure out which of these two paths was the best. That part, of course, was destined to be a serious bitch.

This evening Gretchen and I watched Children of Heaven, an Iranian movie focusing on the miserable life of a pair of poor children forced by bad luck to share a pair of shoes. One grim moment led to another, all building toward a decidedly non-Hollywood ending. Amusingly, the short blurb on the DVD jacket made it out to be a zany romp through the day-to-day lives of a pair of resourceful kids.

For linking purposes this article's URL is:

http://asecular.com/blog.php?090906 feedback

previous | next |